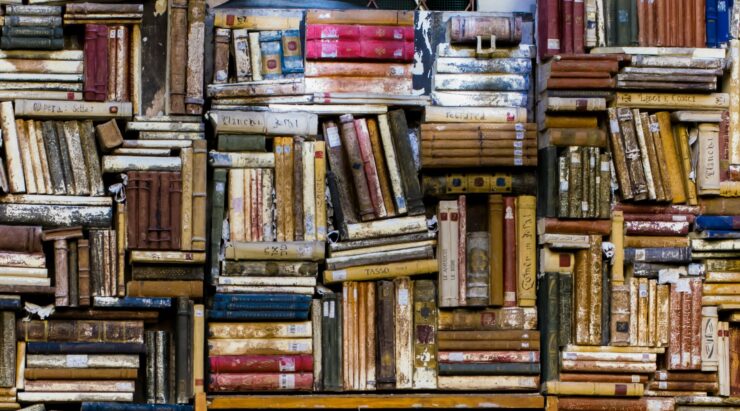

Most days, I look at my books and find a whole mess of positive feelings: Memories of the experience I had reading them; snippets of story; fond thoughts about characters I adored; themes or feelings or ideas that I still carry tucked in my pockets. The unread books are hope, things not yet learned, characters not yet met. The TBR stacks I can never seem to unstack are wishes: I will read this next. I will read this before I start work on that project. I will read this. There will be time.

And some days I want to chuck them all out a window. (Metaphorically speaking. I would never, not really.)

Okay, not all the books. Some? Most? A fraction? It’s not a decluttering urge that brings me to this place, though I understand that temptation, which lurks in the part of my brain that asks Why do you need this are you going to read it again what is it for do you think it looks nice what about this book that there is no room for on the shelf? No, what gets under my skin is something else, something slippery and unavoidable, something I’m trying to be more comfortable with: Mortality. Just plain old ordinary mortality, in the form of a thought: What will become of all of this?

While this isn’t a pressing concern yet—I hope—as I age, as death comes for people closer to me, as the world continues to turn and continues to burn, I find myself wondering: Where is the tipping point? What happens? What do I keep forever? What feels like a piece of who I am? What meaning does this collection have to anyone else?

I am no minimalist. I once joked that if I ever could fit all my stuff in a Mini Cooper, I should be allowed to buy a Mini Cooper, the joke being that this will literally never happen. Most of my stuff is paper: Books, notebooks, journals, copies of a weekly paper I used to work for, more books, yet more books, notebooks stuffed full of ticket stubs and mementos. My books tell a story about who I am, what I value, what matters to me. But it will only matter to me, and only for so long.

And so I keep finding myself thinking about the act, the art, of collecting, of picking and choosing what matters, what we keep, and what—ultimately—we want to deal with later. I think about the digital clutter of unorganized photos, old blogs, little bits of myself scattered around the internet.

Books have always been separate from this train of thought, not a collection but a kind of mental necessity. What is a home for if not to fill it with books? What would I do without them? I can’t get rid of these stories, even though I’ve internalized them. They’re part of me. They’re mine, and the physical reminder of that needs to be here, on the shelf, too rarely dusted.

Does it, though?

My partner and I joke about Swedish death cleaning like it’s a hobby. We don’t have kids; we don’t know who would want our old mementos. Who cares about the weird, massive keychain—a bundle of other keychains smashed together like some terrible mutant—I for some reason carried all through high school? What about cheap earrings in the shape of the Legend of Zelda’s Triforce? What about this old copy of Sophie’s World with the name of everyone I ever lent it to written on the inside cover? Plastic unicorns from the mystery boxes that I can never resist when in the checkout line at Powell’s? What is any of this for?

“Books, even ones I desperately want to read, still have to have a limit. Because truly, the more I buy, the less I read,” Vanessa Ogle writes in “On Book Hoarding and the Perilous Paradox of Clutter.” I have tried to do that math, the math that tracks books in and books read. I tried it for about a month and immediately grew tired of it; it missed the point. The point was that when I buy books, I’m spending money on the idea of the book, the idea of being the person who reads it. If I buy more, do I read less? No, there is always more to read. Always more to buy. There is always another story.

And there’s always another story to tell myself about why I have all these books. They’re my library, my memory; they’re also my nostalgia, for better or worse, for having been the person who read some of these books, and the person who dreamed of reading others. I am comforted by the fact that I will never be without something new to read, but I’m also, absurdly, concerned that I will never read all the things already on my shelves, let alone everything else I want to read. It’s not a real problem. It’s a luxury. But there it is, in my thoughts.

I would like there to be a simple reason for this, a single thing that sent me into a series of thoughts about death and life and what happens to our things, but there isn’t. There is instead an endless series of things: a death in the family, thousands of deaths in the news, the warmest winter on record, piles of discarded fast fashion in other countries, friends’ pets dying, more deaths in the news, war, famine, the list goes on. Maybe, though, it’s not a bad thing to think these slightly morbid thoughts about what I have, what I am, and what happens to all of it. In Make Your Art No Matter What, Beth Pickens talks about “death acceptance,” which is a practice of cultivating a specific relationship to death and grief: “Learning to tolerate and make some peace with the fear and dread is how my brain, slowly and over time, changes to be more in the present, able to endure grief and discomfort.”

Later, she writes, “Where there is death, there is art, and vice versa.”

Sometimes thinking about death acceptance feels like a privilege. Death comes for us all; many of us don’t even have time to think about it. Sometimes it feels like a necessity, for all the reasons Pickens lists. And sometimes, it just turns into thoughts about things, about what we leave behind, about why I have things, whether I want things, whether it’s time to shed another layer or reframe my relationship to what I have and who I am. Most of my trains of thought lead back to stories, in the weird and winding paths of my mind. But the story of a book as an object—the story I impose on my books, whenever I look at them—is not the same as the story it contains. No one else will pick up a specific copy of a book and know the experience you or I had reading it. You can’t pass that on, not without writing it down yourself. What is a collection without its collector?

What do you want to happen to your books? What are they, to you? Are you a keeper or a giver-away, a collector or a borrower? Do they have a future in your family, or with your friends, or on the shelves of the bookstore next door? Does it matter to you? Do you think about it, about what happens to the pieces of a life?